We stared down a toothy ice weasel, smiled at the tumbling moss hedgehogs and tiptoed past the formidable overland sloth wolf. And all the while, our flamboyant and impressively mustachioed host — one H. T. Darling, jauntily attired in a red leather buccaneer coat and feathery headdress — told tales of derring-do in a far flung world.

But what was really amazing, even more than the three-headed hydra snail or the horrific howls inside the Death Cave from Skull Archipelago, was that this evening of immersive theater was happening a block north of City Hall in a historic building that’s largely been dark and disused for 20 years.

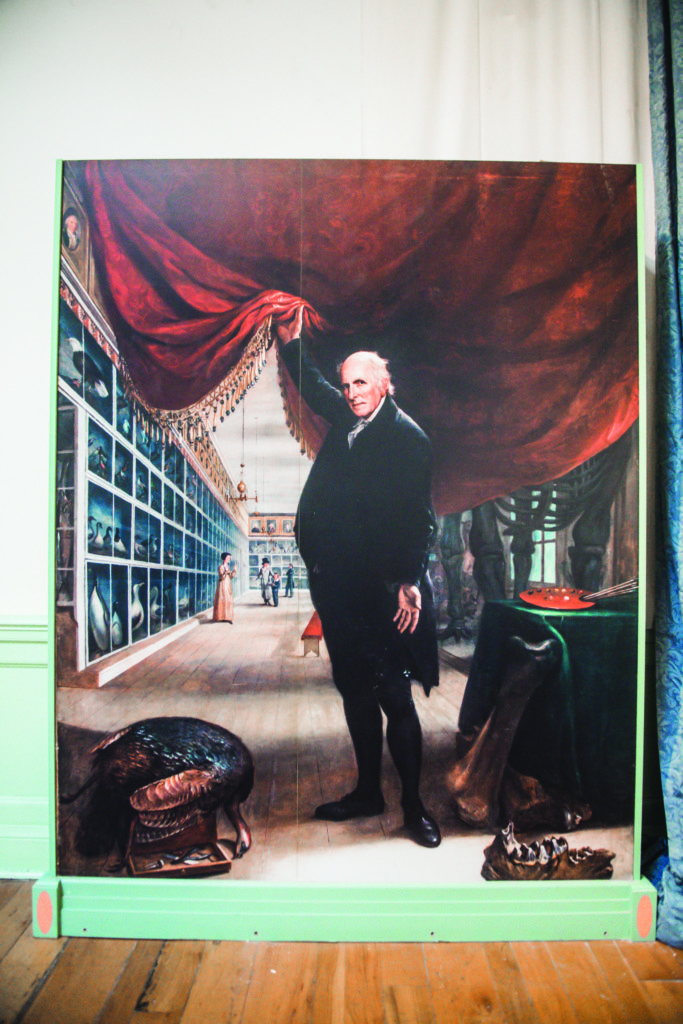

The ancient Peale Museum is back in business. Well, partly. The nonprofit Peale Center for Baltimore History and Architecture is in the middle of a three-phase effort to retrofit the long- mothballed building for 21st century use. It was built in 1814 by artist Rembrandt Peale and is the oldest purpose-built museum in the country. Fundraising and construction are ongoing, with about half of the projected $5.5 million necessary to complete the restoration collected. Meanwhile, the lights are on at 225 Holliday St., the heat and air conditioning work, the bathrooms function and though peeling paint and crumbling plaster abound in some rooms, the building is safe to occupy and artistic events are beginning to trickle back in to the venerable space.

Submersive Production’s show “H.T. Darling’s Incredible Musaeum Presents: The Treasures of New Galapagos — Astonishing Acquisitions from the Perisphere” converted all three floors, and even the attic, into a sort of cabinet of wonders with a dime museum-esque assemblage of stuffed creatures and bizarre artifacts related to the mythical planet (yes, planet) New Galapagos. The show included puppetry, sound and lighting effects, and ringleader Darling and his minions performing skits and talks as patrons wandered around the Peale at will for a night of choose-your own-adventure theater. Crazy as it sounds, it was a good fit for the museum, since Peale’s original 1814 museum also featured stuffed exotic creatures and assorted natural history oddities.

“[Peale’s] collection of things that was both wondrous and strange perfectly suited the idea of our show that the museum be filled with objects and creatures procured from outer space,” says Submersive Production co-artistic director, Ursula Marcum.

“[Peale’s] collection of things that was both wondrous and strange perfectly suited the idea of our show that the museum be filled with objects and creatures procured from outer space,” says Submersive Production co-artistic director, Ursula Marcum.

“We say that the building contributed just as much to the show as we did, and it is definitely one of the characters within it.”

During a quieter daytime visit, some of the folks behind the effort to revive the grand dame arrange to show me around. On hand are Peale Center board president Jim Dilts (an architecture historian, author, and former Baltimore Sun scribe) and executive director Nancy Proctor, whose past employers include the Smithsonian and the Baltimore Museum of Art. As this is a city-owned property, also in attendance is Jackson Gilman-Forlini, historic properties program coordinator for Baltimore City Department of General Services.

“From the city’s perspective, we’d like to retain ownership, but we are committed to seeing this building reopened and put back to use,” Gilman-Forlini says. “We really can’t do it without investment from the community and working in this public-private partnership.”

If it all comes together, the Peale Center will operate the building under a dollar-a-year lease. To date, the city has spent nearly $800,000 for the first phase of the renovations: roof replacement, masonry repair, heating and AC systems upgrades and WiFi installation. The Peale Center, meanwhile, recently launched phase two by outlaying $330,000 for ongoing exterior masonry work and window and door replacements. Phase three is the real kicker: The group will need nearly $3 million to install an elevator (the single biggest expense) and new second floor bathrooms and put in a ground floor café, among other efforts to modernize the 10,000-square-foot building and make it accessible. They’re aiming for a 2020 completion date.

How did we get here? How did this historic gem designed by noted architect Robert Cary Long Sr. become so neglected? To be fair, the Federal-style edifice has had a rocky history. It was only a couple of months old when Rembrandt Peale and his family huddled within amid the threat of imminent British invasion and the sounds of bombs bursting in air drifting over from Fort McHenry. The Brits were stopped, of course, but the Peale family ultimately didn’t have the greatest financial success running the museum and creditors forced its closure in 1829. This, despite Peale having successfully illuminated the building with gaslights in 1816 and having been an early investor in what would become Baltimore Gas and Electric. (It was once said of Rembrandt Peale that as a businessman he proved a good artist.) Another low point came in the 1920s, when the tired building was slated for demolition. Instead, during the Depression, the city coughed up for a detailed restoration, incorporating period wood, marble and trim. It then functioned as the Municipal Museum for decades.

How did we get here? How did this historic gem designed by noted architect Robert Cary Long Sr. become so neglected? To be fair, the Federal-style edifice has had a rocky history. It was only a couple of months old when Rembrandt Peale and his family huddled within amid the threat of imminent British invasion and the sounds of bombs bursting in air drifting over from Fort McHenry. The Brits were stopped, of course, but the Peale family ultimately didn’t have the greatest financial success running the museum and creditors forced its closure in 1829. This, despite Peale having successfully illuminated the building with gaslights in 1816 and having been an early investor in what would become Baltimore Gas and Electric. (It was once said of Rembrandt Peale that as a businessman he proved a good artist.) Another low point came in the 1920s, when the tired building was slated for demolition. Instead, during the Depression, the city coughed up for a detailed restoration, incorporating period wood, marble and trim. It then functioned as the Municipal Museum for decades.

Most recently, Peale’s building was caught up in the City Life Museums

debacle of the 1990s. Back then, ambitious plans were launched for it to join a

collection of city-owned historic sites — including the Shot Tower, Carroll Mansion and the H. L. Mencken House — to be collectively managed as an independent nonprofit: The Baltimore City Life Museums. Its centerpiece was an $8.4 million, iron-fronted exhibition center on Front Street whose displays included a life-size White Tower coffee shop. Unfortunately, attendance figures and revenue never reached projections, debts mounted and the whole well-intentioned, if poorly orchestrated, effort went belly-up in 1997. Most of the art and artifacts ended up with the Maryland Historical Society. The Peale returned to city purview and fell dark. For a time it was rebranded The Kurt Schmoke Conference Center.

“It never really operated as such, in part because it wasn’t ADA compliant,” Dilts says. “It was a conference center in name only and it wasn’t high on the city’s priority list. You know, they had lots of other things on their mind: police, fire department, schools.” (In other words, City Hall was able to overlook a building that was a block away and had actually served as City Hall for a time starting in 1830.)

Citizen-led efforts to reopen the building date back to 2002, and Dilts was among those who formed The Friends of the Peale in 2005, a precursor to the current nonprofit. The new Peale Center will feature permanent exhibits on Baltimore art, history and architecture and will also be a center for storytelling through the program Be Here: Baltimore, which empowers citizens to collect and tell stories through audio, video and even phone apps. Much of the space will remain for rotating art and history exhibits and programming.

One example was “Birdland and the Anthropocene” that ran in October 2017. This 30-artist show was conceived by Baltimore artist and avid birder Lynne Parks and featured bird-themed art and natural history exhibits and performances calling out mankind’s negative impacts on the avian world.

“We have an embarrassment of riches in Baltimore in terms of creative people and artists, and there are so many amazing ways we could host them,” Proctor says. “I think we’ll probably prioritize shows like H. T. Darling and Birdland that have a connection to the building’s past and that are better here rather than some other venue. We get calls every week — sometimes every day — from people who want to use the building and we’re not really even advertising it yet.”

“If we’re doing this well when we’re closed,” Dilts adds, “just think what we can do when we get it open.”

I am thrilled and excited about the reopening of our beautiful Peale Museum!